Artist Interview: Nirit Takele

Interview conducted in 2020

This interview, conducted by writer and curator Charles Moore, was published in Israel's Transformative Black Artists, a book by Moore of interviews with six Ethiopian artists from Israel. Research for the book was conducted during Moore's participation in Artis' Curatorial Residency Program in 2020.

Charles Moore

What can you tell me about your village in Ethiopia and your experience moving to Israel?

Nirit Takele

The little I remember about Ethiopia is mostly from stories I heard. We lived in Bahia Dar in the village called Kunzla where we were farmers. My father though was engaged in weaving fabrics at the time. Mom was a homemaker; if we lacked anything, she would go to the market and barter with the colorful trays she made of straw and wool.

My family and I made Aliyah to Israel in 1991. I remember being in a boat on Lake Tana with my uncle, Dad’s big brother. The journey included a four-day walk from Conzela village to Addis Ababa, the nation’s capital, where the Jews had been gathering before the grand ‘Operation Solomon.’ We waited there three months before the air lift. I do not remember the flight to Israel, but I know from my father’s stories that each family received a single number, which was pasted on their foreheads. Our number was Three. My father left later on another flight because he was in an ‘auxiliary force’ in the Aliyah operation.

What I do remember is that we were accommodated in a hotel in Jerusalem, where we were given Israeli food like Eshel, cheese and eggs. Everything looked so blandwithoutspices. From Jerusalem we moved to the absorption center in Rehovot in the Oshiot neighborhood, where we reunited with my father and stayed for a year.

After 27 years I was seeing Ethiopia again when in 2018 I participated in an artist residency program in Addis Ababa. It began with a proposal to participate in an Israeli ‘Culture Week 70 Years,’ at the invitation of the Israeli Embassy in Ethiopia. This became a two-month residency program initiated and accompanied by Eliyah Mahert Solomon.

One day I flew to visit the village where my family lived. The area by the river was etched in my memory and the moment I saw that river the memory came alive. It was like closing a circle with the place that had hitherto been vague. And there we also met a childhood friend (a Christian man)of my father who excitedly shared about his growing up, mentioned familiar names and sent warm wishes to my family members. This encounter gave me a strong sense of connection to the place.

Nirit Takele, Addis Line, 2018, acrylic on canvas, 100x100 cm.

Charles Moore

When did you learn Hebrew?

Nirit Takele

I came to Israel at the age of six and in the absorption center in Oshiot at Rehovot, I started to learn Hebrew. I continued learning Hebrew at the Elementary School like everyone my age when my family moved to Ofakim in the south.

CM

Discuss with me your time in art school at Shenkar College?

NT

I can say that the four years at Shenkar were extremely challenging but I really enjoyed my time there. I loved getting to experiment with different materials with which art can be created. It was like putting a kid in a playground. So you research and experiment. The first year for me was the most productive because it was the discovery stage. This was an essential stage where you had to be creative in every field—sculpture, print, video, and so on. Over the course you would then choose the area that most appealed to you.

My teachers’ reviews were an important part of our learning because they gave us a lot of guidance. Over time, I realized since creative work is subjective to the viewer, it is important that you develop confidence in your own work and being true to yourself in the way you present your art.

I also gained knowledge about the history of art. I was exposed to a lot of artists’ works, which allowed me to see the bigger picture of the things that artists were contending with in their own culture.

Interestingly, it was in the art history class that I became conscious of a gap between my expectation and what was presented in the curriculum. I mean, I scanned the paintings of the grand masters for characters whose appearance was like mine—dark-skinned people. As a painter I wanted to see the painters’ color palette when they painted dark skins. Unfortunately, dark-skinned people were on the fringes of the picture, usually in the role of a slave, not the main subject. I did not feel this represented me at all and the characters I wanted to portray. And as the single dark-skinned student in class— sometimes also the only one at the art department—it was very important to me to study how people of color were portrayed. I know the power of visibility, but in the history of art, dark-skinned people were not prominent.

So I was not really inspired in how to paint people like me. I actually used the time at the studio to do my research experimenting with colors to create my own dark-skinned people. During the years, I have to admit that some of my teachers did mention here and there a ‘black artist’ in the contemporary art field. That became important to me as I could now see a different perspective of dark-skinned visibility.

During my studies, I took several part time jobs to pay the rental, purchase quality art materials and to partially finance my college degree. I was a cashier in a supermarket, an independent face painting artist and a waitress in the cafeteria of the Tel Aviv Museum. It was very hectic but I made it!

CM

What about the first time you exhibited your work and the collector who bought your work?

NT

In my third year of school I participated in an elective course, at the end of which we held an exhibition titled “Come To Bat-Yam,” at the Ribak Museum, Bat-Yam. It was exciting. I was in the open space with guests when my friend and teacher called me to quickly come in. The then Shenkar President Yuli Tamir wanted to see the student who did the work because she loved the piece and wanted to purchase it for the school collection. I did not expect a painting done as part of my course assignment to go into any collection. What a pleasant surprise!

CM

How do you conjure up these images you paint?

NT

The inspiration can be an event from daily life, a memory or a conviction that I want to convey through my art. Before I paint I consider whether the painting should have one or more characters, and whether the characters are going about some activity or are still. Then I think of the frame in which the characters are set, and how much of the space they will occupy. I then consider the composition. If there are a number of characters, I do a sketch in pencil. If there is only one, sometimes I get straight on to the canvas.

The form will be composed from the memory I have about the human body and, if necessary, I will also change the proportions of the body to the final effect I want to achieve. I sometimes merge the figure with the shapes and colors of the whole painting, and I have to remind myself to bring out the shape of the figure. Second, the figure will be in the color I want to use, color that I may have missed seeing in my mental picture, but I want to bring it out here. But it can all happen for me in my imagination.

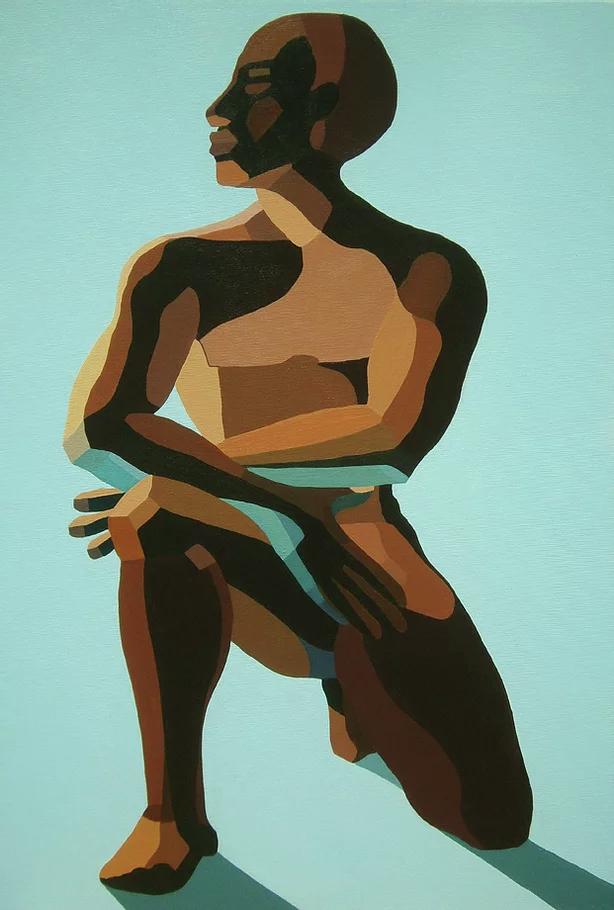

Nirit Takele, Justice for Yosef Salamesa, 2016, acrylic on canvas, 75x55 cm.

CM

Why do you use certain types of imagery and what message do you want to communicate about Black people in Israel?

NT

In my paintings, I am interested in the spots of color and shapes within the figure. When I form the head, I also sculpt the figure (I really liked sculpture in Shenkar). I feel like I am building a figure somewhere between the abstract and the realistic.

I feel comfortable painting on large canvases, which allows me wider and looser movements. So, too, the figures can take on a human dimension or even be like giant sculptures. The characters are mostly muscular men and women alike. As in social realism I want to show these characters as being full of power, and size expresses their inner, heroic strength. This is how I see my community and this is the representation I wanted to convey in my art.

Since there is a tendency for the media to single out the community mainly where there are volatile events such as demonstrations or violence, this both defines and stigmatizes the ‘Beta Israel’ community. Israel is made up of many minorities and this move deprives it of the many facets that a community so rich in history can contribute to the rest of Israeli society.

Art like other visual media is also a tool of communication. For me, it gives me an opportunity to tell a story from my own perspective to expand the dark-skinned figure representation.

CM

Who are some of the artists, past and present, that you admire and how, if at all, have they influenced your work?

NT

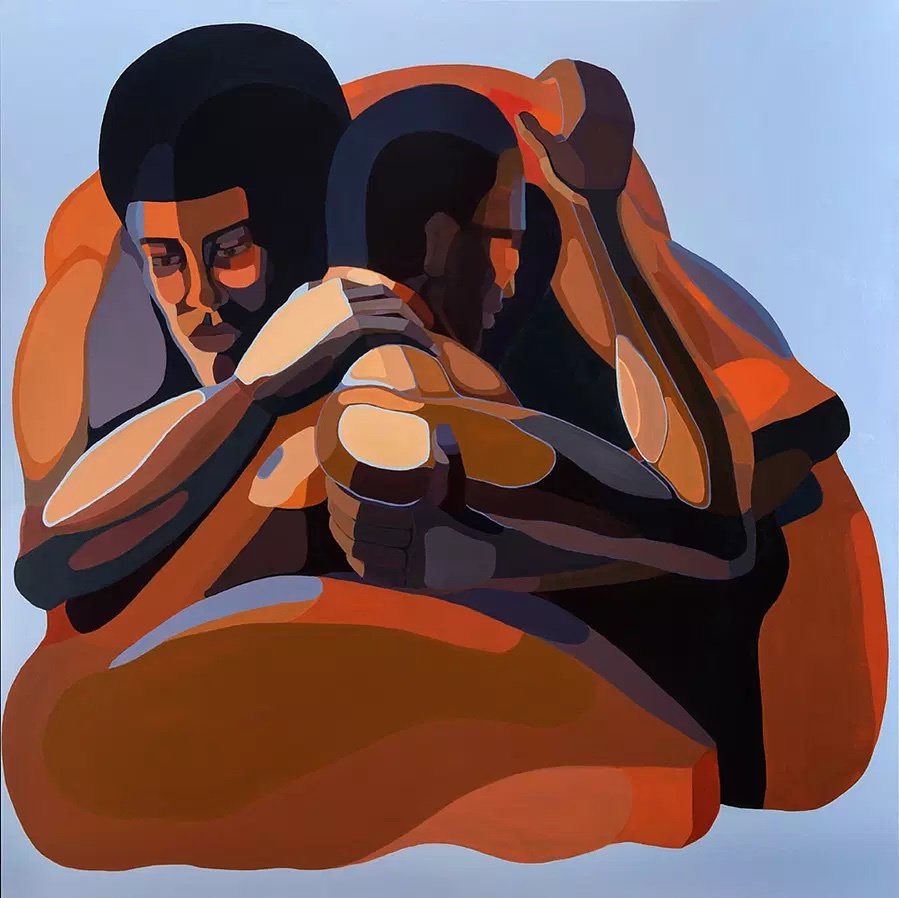

Nirit Takele, Father & Son, 2017, acrylic on canvas, 150x150 cm.

There is no specific artist I can point to that I can say has influenced me. But I do like the sculptural figures of Michelangelo, the colorfulness of David Hockney, and I connect with the paintings of Diego Rivera.

CM

I’m going to select a few images and I would like you to give a detailed explanation of them, the process, how you conceived these ideas, and the techniques used:

Black Box, 2015, acrylic on canvas, 150x150cm.

NT

Israeli society is made up of many communities converging from all over the world. There are many jokes about these diversities showing how complex and rich the reality of Israeli society is. Unfortunately, sometimes these jokes are loaded with offensive nuances. There was one joke that caught my attention, told by a person of Israeli-Ethiopian decent, so I made a drawing based on it.

Even though it started out as a joke, this form and the figure that fills the canvas is still alive in me to this day, though in a different sort of way. It has become a pillar of strength that expands into the territory. The story fits into my desire to paint a figure somewhere between the realistic and the abstract.

Nirit Takele, Mikveh, 2016, acrylic on canvas, 180x90 cm.

CM

Mikveh, 2016, acrylic on canvas, 180x90 cm.

NT

This painting is a protest against the attitude of the rabbinate in Israel towards the ‘Beta Israel’ community of Ethiopia and the forced conversion they had to go through. I describe the humiliation experienced by the women who were forced to be immersed in the mikveh ritual as part of their conversion, even though they lived as orthodox Jews in Ethiopia and had already observed all the mitzvots, from simple to severe, including mikveh. The painting is based on the personal testimony of a woman that made Aliyah in 1984. She described the double humiliation she felt when she was forced to go through the mikveh, with only a white transparent dress covering her, which clung to her wet body in front of her rabbi teachers.

CM

Justice for Yosef Salamesa, 2016, acrylic on canvas, 75x55 cm.

NT

I painted the figure of Yosef Salamesa that has become also a symbol of police injustice towards Israeli-Ethiopian people. Yosef was a young Israeli of ‘Beta Israel’ descent, whose attack by the police led to his death. The painting shows his face in profile. The sitting position is inspired by a painting of Pharaoh by a Canaanite prisoner I saw in the Israel Museum exhibition. In my work, the hands are in an X-position, a protest symbol used by Israeli-Ethiopian Jews against police violence on dark-skinned civilians.Yosef Salamesa is portrayed with a defiant chest and a raised neck to say he was innocent.

Nirit Takele, Black Box, 2015, acrylic on canvas, 150x150 cm.

CM

Father & Son, 2017, acrylic on canvas, 150x150 cm.

NT

The painting deals with the reunion of families who were separated during Aliyah to Israel, in this case, a father and son. Through this painting I convey my personal experience when I met my maternal grandmother after 16 or 17 years of physical separation. When she hugged me, she made me feel like she knew and remembered me, and that really moved me.

Father and Son expresses the pain of separation that was forced on the families of the Ethiopian Jewish community. Many of the immigrants died on the way, and not all of them immigrated together.

CM

Addis Line, 2018, acrylic on canvas, 100x100 cm.

NT

I did this painting during the residency program in Ethiopia. In Addis Ababa I was exposed to amazing sights, which are characteristic of the place: women who work on construction sites, for instance. One common sight is the long endless line of people—people waiting for public transportation—the orderliness and patience they had. It would never work in Israel.

Nirit Takele, Studio visit Adam & Eve , 2019, acrylic on canvas, 160x190cm.

CM

Studio visit Adam & Eve, 2019, acrylic on canvas, 160x190 cm.

NT

This painting is about the story of Adam and Eve and the first artist’s representation of them. That representation has influenced every subsequent image we see in art history because, somehow planted in our subconscious, is the notion that our first parents were white. Even now, if someone were to paint a dark-skinned Adam and Eve, your typical viewer would think, ”Oh, nice, but I know that Adam and Eve are not dark” because in their mind their description comes from the canon of art history, even though the reality can tell a different story.

CM

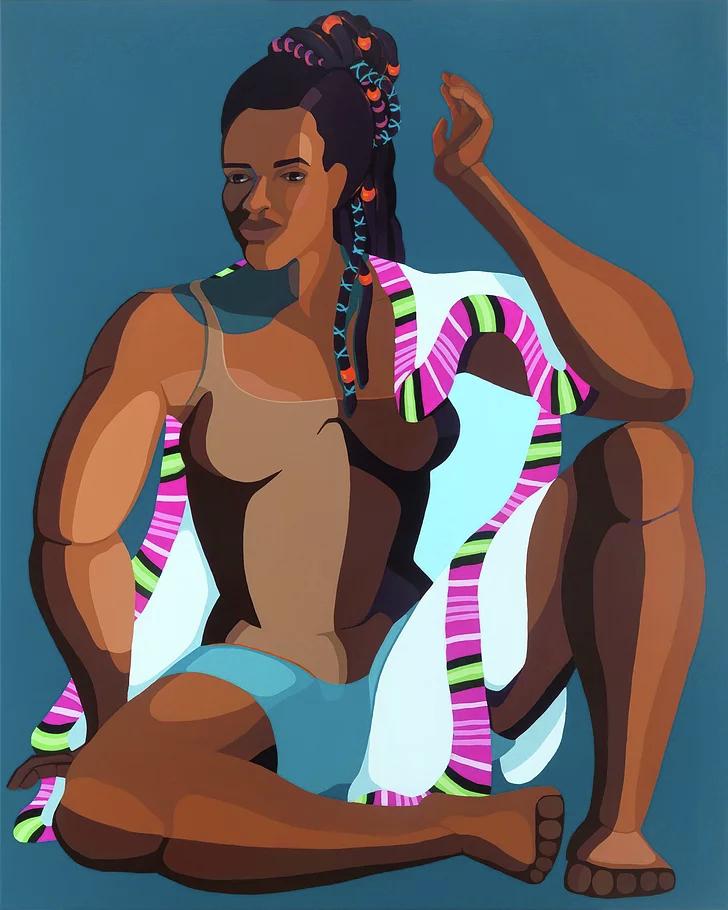

Figure in Shape, 2020, acrylic on canvas, 100x80 cm.

NT

The figure sits in the middle, the traditional Ethiopian attire depicted as straps with different patterns like robes and wraps, flowing around the figure. I attached the traditional fabric to associate with her identity. The character is very muscular and fit, looking very feminist. And the way she happens to sit creates mobility in the body and expands into the canvas frame. She is very busy on the job: no time for dates.

Nirit Takele, Figure in Shape, 2020, acrylic on canvas, 100x80 cm.

CM

You have a window installation coming up in Israel. Tell me about this project and the work you’re putting in it.

NT

The project is a new building, the Ethiopian Jewish Heritage Center in Be’er Sheva. The interior will house:

-The spiritual world of Ethiopian Jews, a space that represents the spiritual story of the Beta Israel community—Halacha, marriage, purity, music.

-An interactive interface that will allow the story of the our heroes to be told: spiritual leadership, heroes of the community, Jewish heroes who influenced the Jews of Ethiopia, breakthrough women

-Some ancient handicrafts attributed to Ethiopian Jews: weaving by men, straw weaving and ceramics on display using artistic elements

-A display case placed in the center of the gallery, where traditional jewelry and a variety of artistic elements will be displayed

-Space for exhibitions – contemporary art

-And the windows I deal with are: 2 windows (286x186 cm.size each)

The paintings will be all about assimilating everyday life in Israel, about the here and now. I have not yet decided what I will paint.

CM

Your next solo exhibition will be in London in November. Which gallery? Have you started thinking about what work you will exhibit?

NT

It will be with the Addis Fine Art Gallery. I prefer not to be limited by definitions and will not determine in advance what I am going to draw to reflect the exhibition theme. My approach is to create intuitively and faithfully according to the moment in time. You see, when I start painting for exhibitions, I do not preconceive a series, so most of the time I still don’t know what subsequent paintings will look like until I get to that stage. Only one thing is for sure: my characters will be as colorful and as dark as me.