From the Desk of… Liliana Farber

Liliana Farber, Terram in Aspectu, 2019, inkjet prints, 11 x 11 inches.

In this interview, artist Liliana Farber writes to us from New York about her research-based practice that investigates the ways in which technology and design inform our perceptions of time and space, and place a significant strain on the environment.

Readings about Liliana Farber’s work

This interview was conducted as part of Artis’ series, From the Desk of…., where we check in with artists about their recent projects, reflections on the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as how they are practicing, experiencing, and engaging with art and current discourse.

In the summer of 2021, you were an artist-in-residence at NARS Foundation in Brooklyn, which Artis supported. What did you work on during your residency?

During my residency at NARS Foundation, my research and work focused on Geographic Information Systems (GIS), like Google Earth, and how these influence our perceptions of space. One of the ongoing themes in my work is the ways that oceans are represented in Google Earth and other GIS platforms. Oceans cover around 70% of the earth’s surface, but because we know so little about the oceans, and there is little data, they are rendered as empty, monotonous space in GIS. I am obsessed with cruising the “digital waters” that are created from compiled data, and then represented visually on these platforms. I zoom in so that the “camera” is placed at a short height from the “sea,” letting the arrows be like the wind, directing my path, as gradients of blue (the “sea”) fill my screen. Most of the data represented on these platforms have no photographic origin, which I find fascinating. Only 5% of the oceans are photographically mapped in the platform. Regardless, we place a lot of trust in information systems.

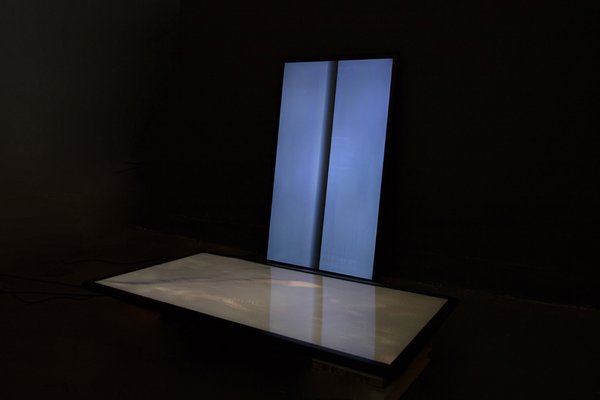

One of the works I developed during the residency is a video sculpture titled Blue Reflections. In this piece, a video presents images of the digital oceans, captured in Google Earth, which are intertwined like the glass pieces inside of a kaleidoscope, a nineteenth-century technology that hypnotizes viewers with its visual effect, created using a chamber of mirrors. This video is projected onto a round steel plate, which is placed on top of a pile of lava stones. In this work, my intention is to share my infatuation with the digital textures that represent bodies of water. When you look at the textures from a close distance, it is revealed that the imagery is an illusion, and does not present reality. I also wanted to make a physical body for the digital mirage. Often thought of as ethereal, the production and maintenance of GIS has a heavy toll on ecosystems. They are operated by infrastructures that are hidden from everyday life, and made of heavy minerals and consume excessive amounts of energy. My project is named after the Spanish saying “espejitos de colores” (colored mirrors), an apothegm that alludes to the exchange of gold for seemingly worthless pieces of colored glass that took place between Spanish colonizers and native civilizations in the Americas. Blue Reflections references the uneven power dynamic between users and platforms and the expense of their artifice.

Liliana Farber, Blue Reflections, 2021, single channel video, steel plate, lava stones.

That is fascinating! What are some of the ecological expenses that are deprioritized, in order to maintain GIS platforms?

Minerals and polymers are used in the construction of the satellites that power the imagery that we see in GIS platforms. This extraction and processing of natural resources is taxing on the environment. For example, nickel and lithium are used in batteries that power these technologies. Nickel extraction causes the release of sulphur dioxide, a toxic gas, and lithium extraction is a demanding process that requires a great deal of water. Kevlar is another polymer that is often used in satellite construction because it is incredibly resistant to temperature changes, but to manufacture it, the extraction and use of toxic sulphuric acid is required. Apart from the environmental costs of the material infrastructure, energy is also an expense for maintaining information systems. Processing information in data centers, such as those that host GIS platforms, produce vast amounts of heat, and this temperature needs to be regulated. The cooling off of global data centers is responsible for roughly 166 terawatts a year (about 1% of the total world’s electricity). These are some examples to show how producing and maintaining a virtual representation of our world affects the physical ecosystem.

What was it like to participate in a residency during the pandemic?

During the pandemic, the world became my little apartment in Brooklyn and I stayed connected to others via my screens. My residency started after more than a year of this solitude, and static lifestyle. Riding my bike to Sunset Park, where the residency is located, to work in the studio, and being among a cohort of artists-in-residence, was a change that I welcomed. There was a special energy between the artists-in-residence. Everyone was excited to be surrounded, by people and in community again, though with masks. For me, this breach of seclusion had a great impact on my studio practice. I worked almost exclusively on sculpture projects. It was like gaining a body after existing as a virtual being.

Reference image for l-a-s-e-n-i-o-r-a-i-n-d-i-c-a-r-a, web app by Liliana Farber (2021). Image is from a contest titled "Search for the Girl with the Golden Voice" initiated for the first speaking clock voice in the United Kingdom, 1936.

Tell us about your online solo exhibition with El Centro de Exposiciones Subte and 1708 Gallery, which launched on November 4.

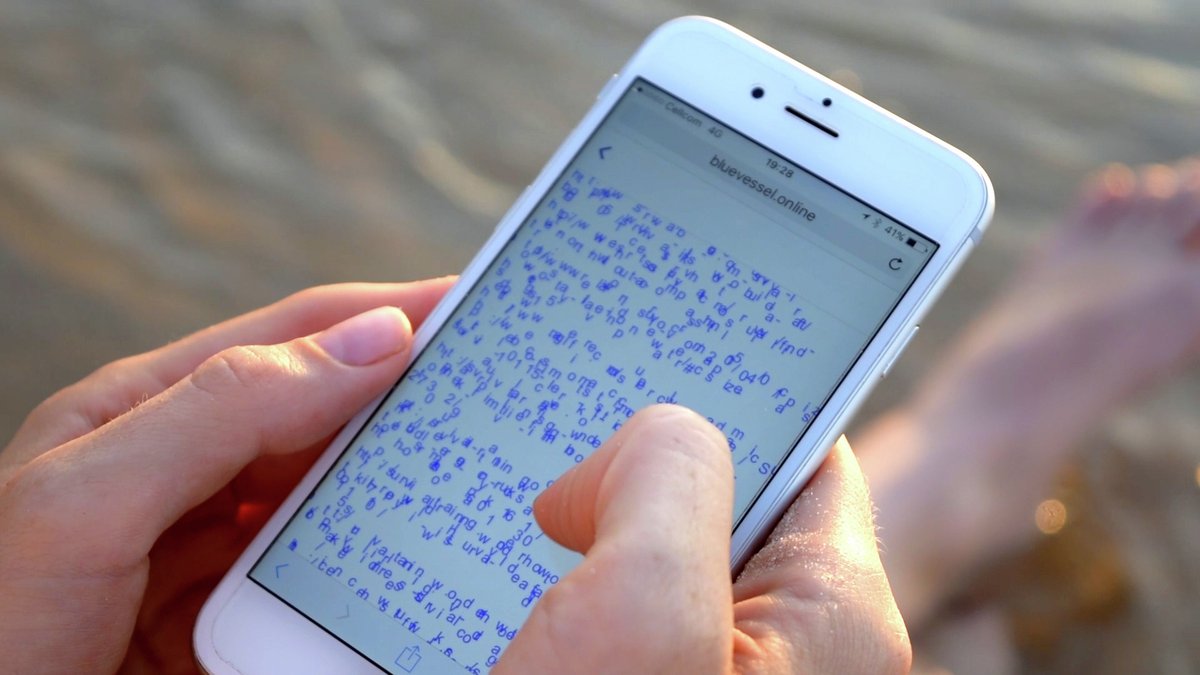

L-a-s-e-n-i-o-r-a-i-n-d-i-c-a-r-a.online is another pandemic born project. This is a net-art work that explores solitude, connectivity, and the weight that time acquired during the Covid-19 pandemic. It is an artwork made to be experienced at home, from a connected device, in this in-between space that we became so used to. A space in which time synchronization is key for its functionality.

The artwork invites users to participate in a mutual understanding contract (user agreement), in which the website and the participants agree to establish a single criterion for time management, based on Western conceptions of planetary, chronological coordination. By participating, each user leaves an indelible time stamp on the site that coexists with the stamps of all past and future visitors, thus creating a chronological multiplicity. It is a reflection on the physical distance that defines the months since the onset of the pandemic in March 2020, while also confronting an illusion of closeness that characterized our movements before the pandemic.

The project, curated by Roxana Fabius, was simultaneously launched by 1708 Gallery in Richmond, Virginia, United States and El Centro de Exposiciones Subte in Montevideo, Uruguay. It was important to launch the project in two different time zones, to accentuate the role of time synchronization when experiencing the world through a screen.

Liliana Farber, Blue Vessel, 2017, mobile web app.

Did you plan and think about the work in this exhibition differently, given its online format?

When the pandemic started, I thought a lot about the concept of time. All of a sudden, time surrounded me, and I felt like we lost the dimension of space. I kept thinking about Paul Virilo’s book “Open Sky,” where he describes this phenomenon that in the cyber-connected world, we don’t share space but we share time. Electronic synchronicity is what keeps us going during the pandemic. We spend our days in a hybrid dimension in-between space and time. I wanted to make an artwork that could be exhibited in that space, and would strip the historical conditions and geopolitical implications of the nature of that space.

Tell us about how you begin a new project. What is your process? What are ideas you explore in your work?

My process involves plenty of reading. Reading, pulling quotes and placing them on my wall, asking questions, falling down the rabbit hole of research. At some point in this process, I start to draw connections between the papers hung on my wall, and then ideas begin to form. While I was thinking about spaciallity during the pandemic, I envisioned a virtual space in which the only interaction users could have is to be there. L-a-s-e-n-i-o-r-a-i-n-d-i-c-a-r-a is a space created just to be.

This work brings together ideas that I have been working on, from past projects: The opacity of digital infrastructures, poetic user agreements, non-interactive interactions, server performances, and the use of time as a data structure to translate lived spaces into digital spaces. In l-a-s-e-n-i-o-r-a-i-n-d-i-c-a-r-a, I continue to explore these ideas with a focus on time construction. What are the algorithms, the institutions, and the materialities that define current time? This artwork is also different from past projects in that I make my research accessible to the viewer. The user agreement at the beginning of the piece acts as a registry of the process that led me to this work, and all the stops and questions that I had along the way.

About the Artist

Image: Liliana Farber.

Liliana Farber is a Uruguayan/Israeli visual artist based in New York City. Using custom software and public digital platforms, she examines the ramifications of histories and design protocols that inform broad perceptions of space and time. Farber is a recipient of the Lumen Prize for Art and Technology, the Network Culture Award from Stuttgarter Filmwinter Festival, and Artis Grant, among others. She has exhibited in venues such as The National Museum of Contemporary Art (Lisbon, Portugal), The National Museum of Fine Arts (Santiago, Chile), The National Museum of Visual Arts (Montevideo, Uruguay), Ars Electronica Festival (Linz, Austria), Arebyte Gallery (London, UK), WRO Media Art Biennale (Wroclaw, Poland), and Raw Art Gallery (Tel Aviv, Israel). Farber’s work has been featured in OnCurating, MIT’s Leonardo, Erev-Rav, Haaretz, and El Pais. Farber holds an MFA from Parsons School of Design (New York), Postgraduate Fine Art Studies from Hamidrasha School of Art (Beit Berl, Israel), and a B.A from O.R.T University (Montevideo, Uruguay). www.lilianafarber.com