From the Desk of… Ilit Azoulay

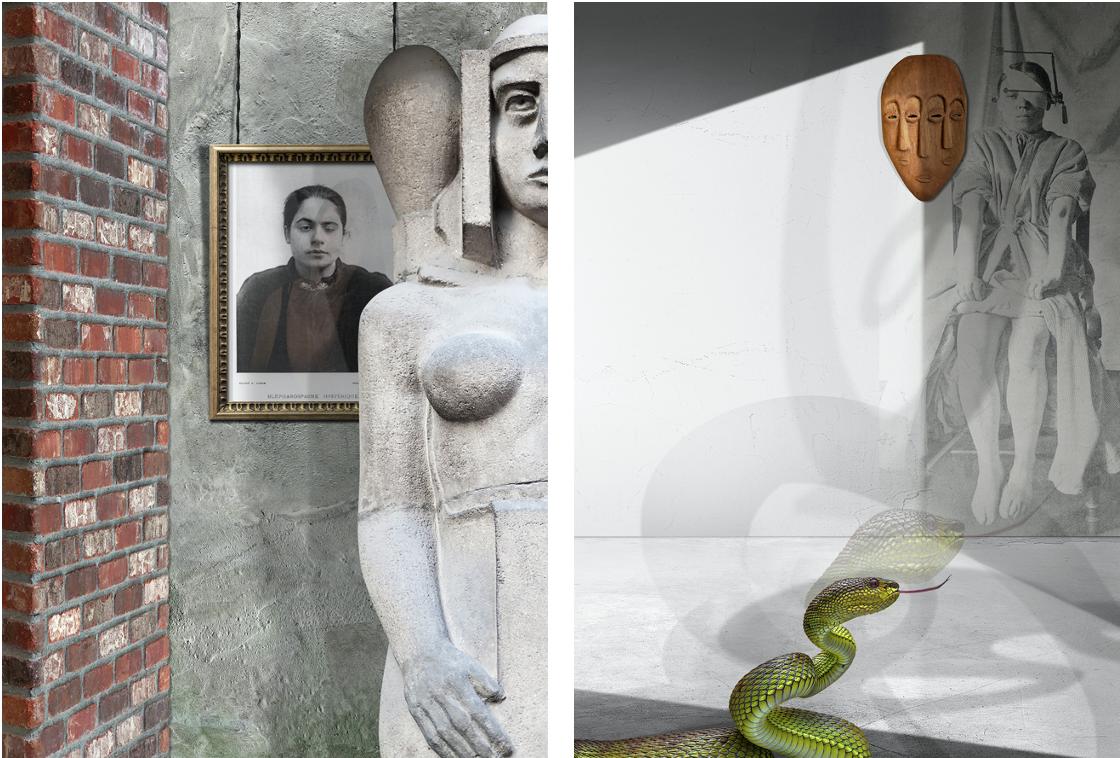

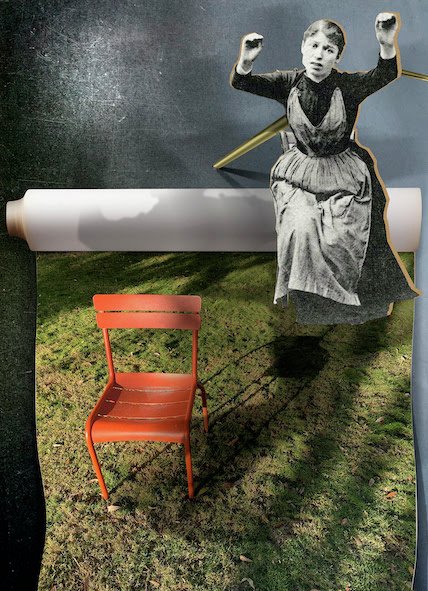

In this interview, artist Ilit Azoulay writes to us from Berlin about how she has adapted her artistic process in response to social distancing regulations. This shift led to her current research into the history of hysteria as a medical diagnosis that targeted women, and the ways in which photography was used as a tool to support this social construct. Ilit creates large scale photo montages that reveal gaps in history. She compiles images of objects and other materials that she encounters while doing field research, and arranges them into digital panoramas that simulate fictitious space.

This interview was conducted in May 2020 as part of Artis’ series, From the Desk of…. In this series, we check in with artists, curators, and collectors about their recent projects, reflections on social distancing and quarantine, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as how they are practicing, experiencing, and engaging with art.

Images of work in progress by Ilit Azoulay, 2020, courtesy of the artist.

Tell us about a project you’re working on now. What kind of research are you doing to develop this project?

Recently, I started working on a project that examines the history of female hysteria beginning in the 19th century, when it was considered a widely diagnosed illness, to the present day, in which the term has been discredited as a medical condition, yet is still used colloquially and in the media.

One of the sources in my research is French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot, who worked and taught at Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris from 1862 to 1895. Charcot founded the hospital’s Neurological Department and installed a photography lab in the hospital for his research. This was one of the first photography labs established in a medical institution. He ran experiments on female patients, who were diagnosed with hysteria, and developed theories based on his photographic research.

In the 1980’s, French philosopher Georges Didi-Huberman wrote extensively on the notion of hysteria. He examined the relationship between photography and psychiatry in the late 19th century, and the ways in which photography was used to construct stereotypes and generate ‘knowledge’. According to Didi-Huberman, hysteria was invented as a medical condition at the Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris in the latter part of the 19th century. Identifying hysteria as a medical condition enabled a mechanism of control, and increased the institutional regulation of an individual’s desires and fantasies. Photography served as a platform to stage and realize a patriarchal dynamic between male clinicians and female patients, and to tie together scientific knowledge, sexual desire, and institutional power. Today, we understand that the notion of hysteria is a social construct of the past, and a system that maintains patriarchy, opening up the possibility for a reevaluation of hysteria as resistance to patriarchal culture.

As a next step in my research process, I would like to examine ways that non-Western cultures—particularly in the East and in Africa—relate to what the West defined as female hysteria. In different communities, this notion may be understood differently and manifest in markedly distinct ways that are connected to healing and spiritual practice, as opposed to sickness and abnormal behaviors.

Has your practice shifted in response to social distancing and quarantine regulations?

When we can travel and move freely without social distancing restrictions, my practice involves fieldwork. I have meetings and conduct interviews where I gather testimonials, stories, and photographs, which are used in my work to reveal gaps in history. In addition, I normally work with a team. But nowadays, given the isolation of home quarantining, boundaries dictate the nature of our interactions, and I am finding new ways of working. Instead of building a repository of images based on my fieldwork, I am looking at ready-made photographs from image banks, and working with existing archives.

In this project, I have been using stock photo images of screwdrivers, countertops, iron rods, pipes, walls, and architectural parts, sculptures, fabric textures, variable weather skies, windows, and more. In my research, I found that one of the image banks that I have been working with contains several thousand images that show the facial expressions of women in distress, or “experiencing hysteria.” These images were used primarily in advertisements. From these, I selected approximately 300 images of “hysteria.” This search revealed considerably more images of women than men. This made me question why there is such a high demand for images of women in distress. From this research, I have developed a body of work that relies on archival research and reading.

Is there anything, in particular, that you miss from life before social distancing?

I miss my studio routine, it is immensely important to me. And I miss hugging people.

How are you staying connected to friends, family, and colleagues? What does community and solidarity mean to you nowadays?

Like most of us, I find ways to meet and chat with loved ones via online platforms. My perception of time has changed, and I enjoy observing its effect on communication with friends and family, the way we listen to each other, and how we try to eliminate the physical gaps we’re experiencing through technology. I am surprised, in a good way, that we are still able to capture and experience so much intimacy with technology.

Jean-Martin Charcot, Iconographie Photographique de la Salpêtrière, Progrès Médical, Paris, France, 1877. Three volume book where Charcot published his research, digitized copy available by MgGill University Library.

George Didier-Hubermann, Invention of Hysteria. Charcot and the Photographic Iconography of the Salpêtrière, The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts, London, England, 1982. Translated by Alisa Hartz, 2003.

Published on May 22, 2020.